Sharia Law

This page was created in equal collaboration between Braden Sciarra and David Harting and was last updated December 4, 2013.

Overview

Sharia Law is a comprehensive moral framework for how a Muslim ought to relate to others, to God, and to themselves. Sharia law is neither monolithic nor entirely tangible, but is somewhat formalized. Legal books exist, but Sharia Law is defined and understood within communities, and differing interpretations are accepted. Many Muslims regard Sharia as personal, a guide to emulating the Prophet’s perfect submission to God in all details of life. On the other hand, Islamic theocracies implement Sharia law as state legal systems.

Although some view current political uprisings for and against Sharia Law as evidence that the Law is static and incompatible with modernity, shura emphasizes continual democratic reinterpretation

(Coulson, 2013; Islamic law, 2008).

Where does Sharia Law come from?

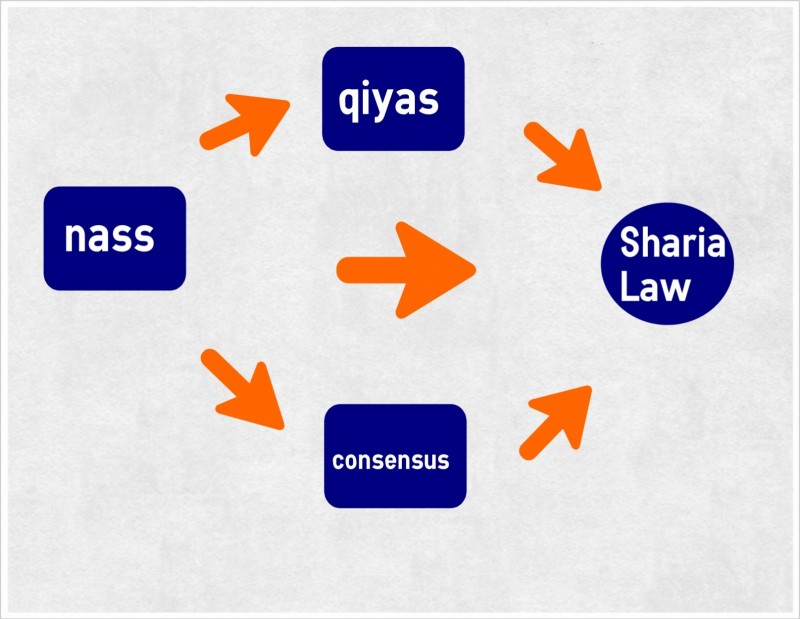

Sharia Law is the law of Allah, rooted in scripture. Reason and analogy are relied upon where scripture does not explicitly apply. (Armstrong, 2000)

Created by David Harting, November 2013.

Based on information from Armstrong (2000) and Islamic law (2008).

Muslims refer to explicit scriptural moral conduct commands as nass. Scholars study these laws, and their collective understanding comprises part of Sharia Law.  Many Muslims believe that God would not allow all of scholarship to misunderstand the Law. Finally, Sunni Muslims recognize qiyas, or analogies from scripture. When scripture does not directly apply to a situation, scholars look for the general purpose behind scriptural moral instructions, and apply these rules. (Islamic law, 2008)

Many Muslims believe that God would not allow all of scholarship to misunderstand the Law. Finally, Sunni Muslims recognize qiyas, or analogies from scripture. When scripture does not directly apply to a situation, scholars look for the general purpose behind scriptural moral instructions, and apply these rules. (Islamic law, 2008)

Who is subject to Sharia Law?

The jurisdiction of Sharia penal law is only the public activity of Muslims. Non-Muslims are not held to these standards, and private behavior is left between the individual and God.

(Islamic law, 2008)

What does Sharia Law cover?

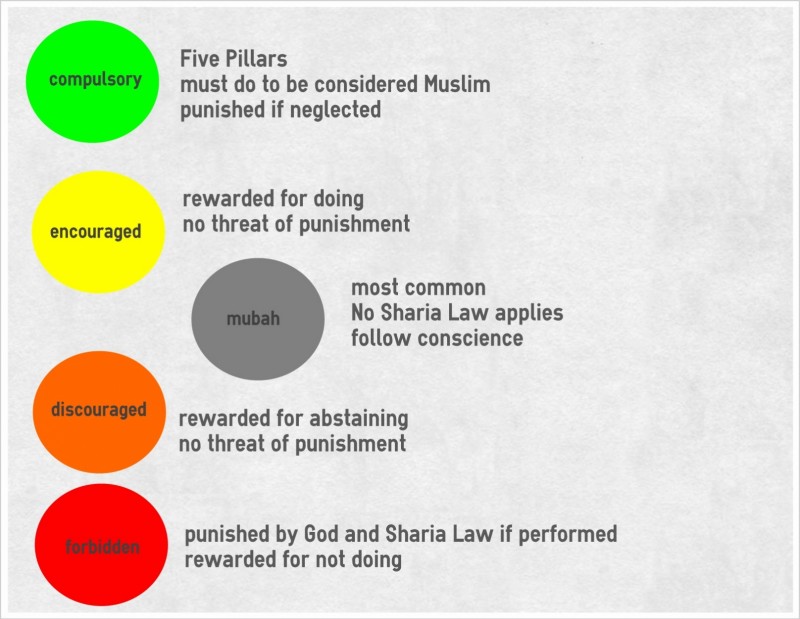

In short, everything. The majority of Sharia Law details obligations to Allah, and most ethical requirements are not subject to legal punishment. Most legal texts begin with the Five Pillars.

However, regulations for human relationships (below), and specifically penal law, attract the most media attention.

Family: regulates marriage, divorce, and guardianship of children.

Inheritance: conservative branches focus on the male line, while liberal branches give equal weight to males and females.

Financial Transactions: prohibits interest, gambling, speculative commerce, and commerce of prohibited goods (e.g., weapons, alcohol); a trillion dollar Sharia banking sector (Johnson & Vriens, 2011) serves Muslims seeking to honor Sharia Law in their financial lives.

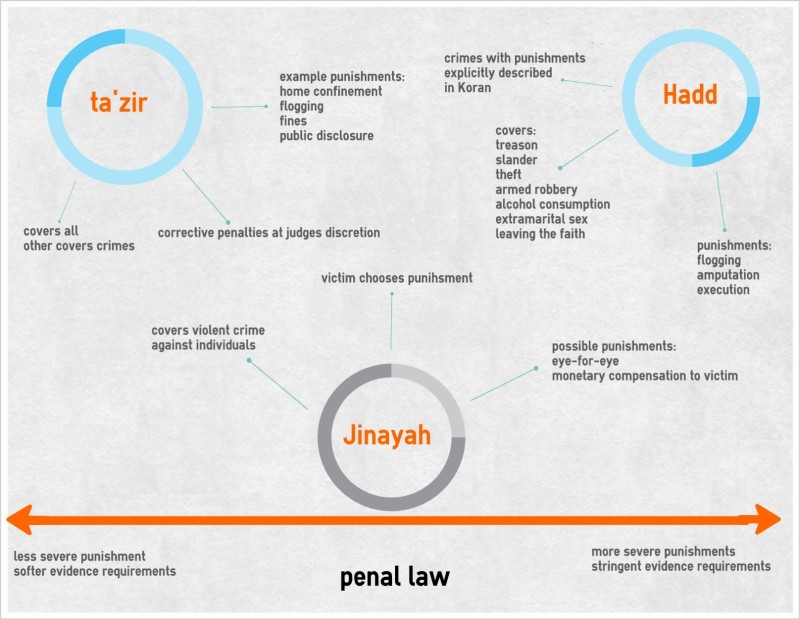

Crime: penal codes specify what constitutes a crime and what punishment is deserved (see visual below)

(Coulson, 2013)

Court Procedures

Sharia courts are run similarly to modern, secular courts: defendants are innocent until proven guilty, and the burden of proof lies on the prosecutor. The case is presented to a qadi, a trained judge, who may be a layman but consults scholars as necessary.

(Coulson, 2013)

Sharia Courts, Schools and Officials

Top Left: Al-Qasemi College of Sharia and Islamic studies (by Ruvenj, July 2012, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Top Right: 14th century painting of an Arab leader pleading with a qadi (public domain)

Bottom Left: Agha Rafiq Ahmed Kan, Chief Justice of Pakistan’s Federal Sharia Court (By Aghaharis, Jan 2012, CC BY 3.0).

Bottom Right: Jamia Shariyyah Malibagh school of Islamic law in Bangladesh. (by Bakrbinaziz, August 2012, CC BY 3.0).

Schools of Jurisprudence

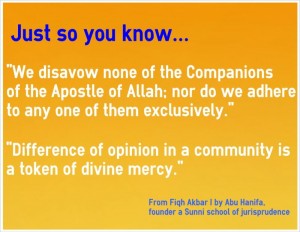

Muslims distinguish between the immutable law of God, Sharia Law, and the fallible interpretation and application of law, known as fiqh, or jurisprudence. There are many schools of jurisprudence, and Muslims may adhere to one or borrow from many.  Conservatives tend to accept only one school, and may only accept medieval scholarship, claiming that the window for interpretation has closed. Modernists accept continuing developments in jurisprudence and may interpret the Koran for themselves. (Islamic law, 2008)

Conservatives tend to accept only one school, and may only accept medieval scholarship, claiming that the window for interpretation has closed. Modernists accept continuing developments in jurisprudence and may interpret the Koran for themselves. (Islamic law, 2008)

Because most Muslims do not adhere to a school in their private lives, the biggest impact of fiqh is on the governments of Muslim countries (Johnson & Vriens, 2011).

Political Implementation of Sharia Law

The degree of integration of Islamic Law into the state varies by country. These approximate categorizations indicate the level of influence.

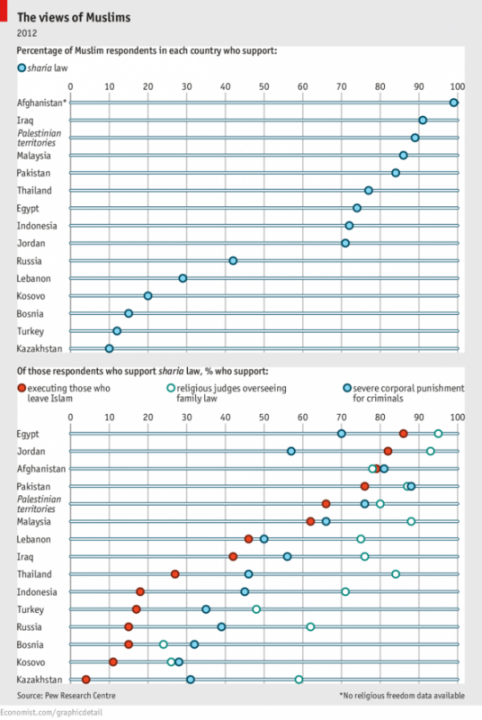

Muslims’ preference for the implementation of Sharia law varies widely, but this Pew data (left) suggests most countries are, on average, liberal or conservative, rather than moderate.

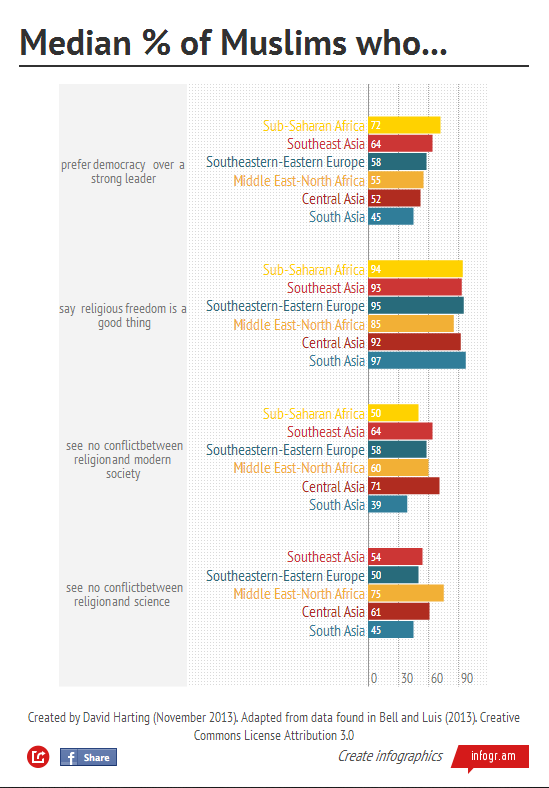

Yet, in most regions, well over half of Muslims prefer democratic governments and believe Islam is compatible with science and the modern world. Nearly all Muslims support religious freedom (see chart below and left).This seems to contradict the previous chart which portrayed many countries as, on average extremely conservative in their desired implementation of Sharia law. However, this could suggest that conservative Islam is indeed compatible with democracy and Sharia law. Perhaps many conservative Muslims believe that strict Sharia law should only be enforced on those who choose to subject themselves to it, or those who are Muslim. Another possibility is that the Muslim respondents simply have a different idea of democracy and religious freedom than Westerners.

Close Up: LGBT Rights

Muslim Women in Hijabs Complete covering is required in some Muslim countries, while some women freely choose to cover themselves. Although this does not directly relate to LGBT rights, it exemplifies what some interpret as evidence of patriarchy and oppression in Islam.

Left: Taken Sept 2008 by Jarek Jarosz, CC BY-NC 2.0

Middle Top: Taken May 2011 by Abhishek Srivastava, CC BY-NC 2.0

Middle Bottom: Taken June 2012 by Aslan Media, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Right: Taken March 2011 by Simon Ingram, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Overview

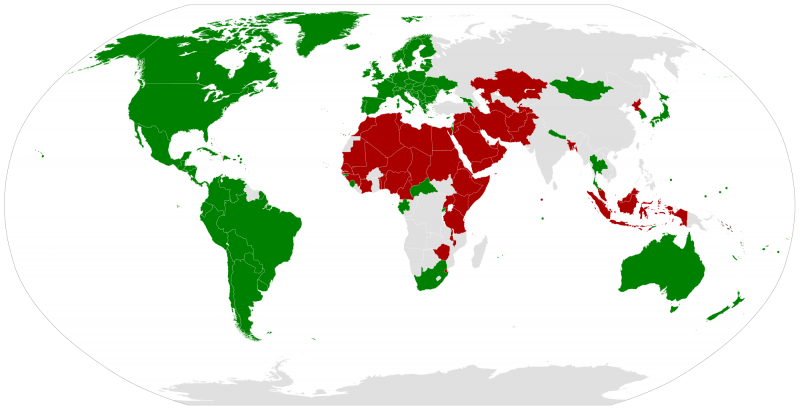

Support for the UN charter on LGBT rights Supporters in in green, opposition in red. Note the concentration of opposition in the Muslim world. Image released to public domain by anonymous creator. Created April 2013. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons November 2013.

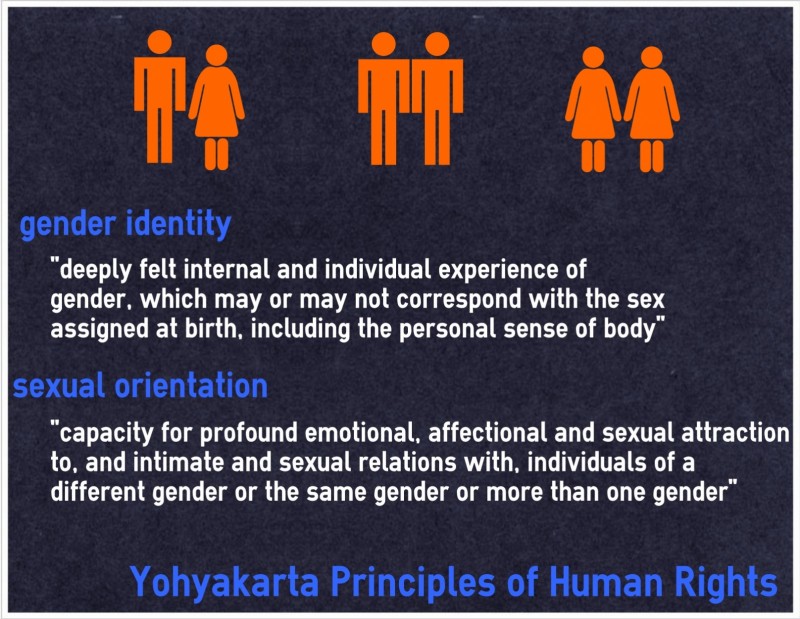

Sharia Law is principally associated with a patriarchal, heterosexual society founded on the Koran. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that with regards to liberal topics such as homosexuality and gender diversity, Sharia Law yields adamant opposition. In traditionalist states where leaders deem these human rights issues insignificant, these terms are not adequately defined. The International Commission of Jurists, a human rights group, sought to close that gap (see visual below).

(ICJ, 2007)

Homosexuality in the Koran

The Koran includes several references to the issue of homosexuality, in particular a reference to the Tribe of Lot—ultimately killed by Allah for their lustful homosexual acts between men. The Koran describes homosexual acts [liwat] saying, “do you commit the immorality that no one in the wide world has done before you?” (Q.7:80). Reference to this particular passage has served as primary justification for the punishment and illegality for homosexual acts throughout history.

The Koran

Left: Taken February 2013 by WEB Chicago Public Media, CC BY-NC 2.0

Middle: Taken March 2007 by Dave Rutt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Right: Taken February 2009 by Ozgur Mulazimoglu, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Some early Islamic leaders, such as the second khalifa, ‘Umar, “insisted that the Koran did in fact specify the stoning as the punishment for hadd crime.” However, despite the clear opposition for liwat in the Koran as seen in the story of Lot, “there is no explicit command in the Koran to stone someone to death either for homosexual intercourse or for adultery [zina].” Ultimately, the various schools of law differ in their punishment; some say the penalty for zina and liwat are the same citing the Koran, which indicates that both are considered an “immorality.” More conservative schools of Law tend to lean towards a more radical approach—execution—as seen in the story of the Tribe of Lot.

(Siraj al Haww Kugle)

Modern Sharia Law and LGBT

Modern Sharia states acts to suppress the visibility of LGBT citizens and organization in society. As previously mentioned, historically there is no reference to sexual orientation and gender identity in Sharia law, strongly indicative of the heterosexual patriarchal society. Therefore, sexual intercourse between males has been roughly categorized as zina, or adultery—this offense is therefore considered to be a hadd offense. According to a study by Dr. Vanja Hamzić, “sexual orientations and gender identities outside the new hetero-normative standards have been largely outlawed in Muslim-majority states.”

Muslim supporting LGBT rights

Note that all images are from demonstrations in Western countries. Images of such demonstrations in predominantly Muslim countries, especially those under Sharia rule, could not be found. In such countries the social and legal repercussions may be too severe for demonstrations to occur.

Top Left: San Francisco Gay Parade 2008 (Franco Folini, June 2008, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Top right: London (Charles Roffey, July 2008, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Middle Left: London World Pride 2012 (lewishamdreamer, July 2012, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Middle Right: London 2010 (Peter aka anemoneprojectors, July 2010, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bottom: London World Pride 2012 (lewishamdreamer, July 2012, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Some believe that this is a way for Islamic states to oppose “westernization” and western liberalism. As of 2009, gender transitions and same-sex sexual acts were officially illegal in 27 Islamic states. Today, homosexual acts carry the death penalty in Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Iran, Afghanistan, Mauritania, Somalia, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, and the South Sudan. Although there is stark opposition to the LGBT presence in a significant number of countries, it is important to not that this is not the case for all Sharia Law states. Some states such as Turkey allow liwat and other nations are have substantial support against anti-LBGT legislation.

(Hamzic, 2011)

References

Armstrong, K. (2000). Islam: A short history. New York: Modern Library.

Bell, J. & Lugo, L. (2013). The world’s Muslims: Religion, politics, and society. Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/files/2013/04/worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-full-report.pdf November 20, 2013.

Coulson, N. J. (2013). Shari’a. In Encyclopedia Brittannica (Academic Edition). Retrieved from http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/538793/Shariah

Economist.com. (April 30, 2013). The views of Muslims. [Chart]. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2013/04/daily-chart-20 November 20, 2013.

Hanifa, Abu. (2009). Selected Fiqh. In Global and Historical Studies Program, Butler University, Change and tradition: China and the Islamic Middle East (2nd ed.). New York: Pearson Custom Publishing.

Hamzic, Vanja. (2011). The case of ‘queer Muslims’: Sexual orientation and gender identity in international human rights law and muslim legal and social ethos. Human Rights Law Review 11(2): 237-74.

International Commission of Jurists (ICJ). (2007). Yogyakarta Principles – Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity. Retrieved from http://www.refworld.org/docid/ 48244e602.html [accessed 21 November 2013].

Islamic law. (2008). In Need to Know? Islam. Retreived from https://ezproxy.butler.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.credoreference.com/entry/collinsislam/islamic_law Chicago, November 2013.

Johnson, T., & Vriens, L. (2011). Islam: Governing Under Sharia (Backgrounder). Retrieved from Council on Foreign Relations website: http://www.cfr.org/religion/islam-governing-under-sharia/p8034.

Siraj Al Haww Kugle, Scott. Homosexuality in Islam: Critical reflections on gay, lesbian, and transgender muslims. Oneworld Publications.