The Koran

History:

The Koran is believed by Muslims to be the word of God as delivered to the Prophet Muhammad. He was born about A.D. 570 in Mecca, which is in present-day Saudi Arabia and died in A.D. 632. His parents were traders and Muhammad spent his childhood traveling all around the Middle East, exposing him to a diverse set of cultures and beliefs. He rejected the widespread polytheism of his day, he instead turned to the one God worshiped by the region’s Christian and Jewish communities.

At about age 40 Muhammad retreated to a cave in the mountains outside Mecca to meditate. There, Muslims believe, he was visited by the archangel Gabriel, who began reciting to him the Word of God. Until his death 23 years later, Muhammad passed along these revelations to a scribe and a growing band of followers, including many who wrote down the words or committed them to memory. These verses, compiled soon after Muhammad’s death, became the Koran, or “recitation,” and are considered by Muslims to be the literal Word of God and a refinement of the Jewish and Christian scriptures (Belt, 2002).

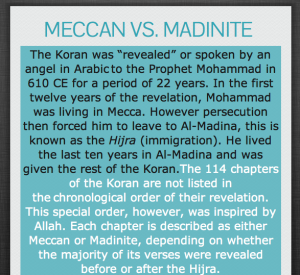

Breaking Down the Koran:

Click the image above to be taken to an info graphic detailing the two categories of verses in the Koran!

History of Koran Calligraphy:

In Islamic culture the art of book making holds pride of place. The Muslims have always been enamored of beautiful calligraphy, and the bold, striking Kufic script lends itself to great art. This passion was reinforced by the fact that the first duty of the scribe was to write out the Koran, the Word of God to the Muhammadan – it was a holy act, even the pen was set apart. Both artists and craftsmen devoted their lives to the production of copies of the Koran which were as perfect as could be devised in materials, bindings, and calligraphy. A religious and literary inspiration was the fountainhead of their artistic achievements. It gave them a strong sense of design, balance, purpose, and of reverence for the pen and the scribe, whose work was so much above that of the painter in general esteem because the latter concerned himself with the secular, with ”images.”

Being thus a melancholy lot, the Iranians were eager to find ways to escape from their dread of calamity, and particularly liked pictures that emphasized the agreeable. They wanted to be reminded of their gardens – which they adored – of airy pavilions by flowing water: and the people who could enjoy these settings wanted to see colour and flowers. This was natural, as Iran is a floral paradise – especially of roses – and, as for colour, even the terrible mountains glow in tones of pink, mauve, and blue in that high clear air. (beauty Balanced)

Arabic Calligraphy and the Naskh Script

Origin of Arabic Calligraphy:

According to contemporary studies, Arabic writing is a member of the Semitic alphabetical scripts in which mainly the consonants are represented. Arabic script was developed in a comparatively brief span of time. Arabic became a frequently used alphabet–and, today, it is second in use only to the Roman alphabet.

The early Arabs were basically a nomadic people. Their lives were hard before Islam, but their culture was prolific in terms of writing and poetry. Long before they were gathered into the Islamic fold, the nomadic Arabs acknowledged the power and beauty of words. Poetry

for example, was an essential part of daily life. The delight Arabs took in language and linguistic skills also would be exhibited in Arabic literature and calligraphy. The early Arabs felt an immense appreciation for the spoken word and later for its written form.

Arabic script is derived from the Aramaic Nabataean alphabet. The Arabic alphabet is a script of 28 letters and uses long but not short vowels. The letters are derived from only 17 distinct forms, distinguished one from another by a dot or dots placed above or below the letter. Short vowels are indicated by small diagonal strokes above or below letters (Chemnad, 2006)

Naskh Script:

Nothing is comparable to love. Nothing is comparable to the love of wisdom. Arabic calligraphy was originated to crown the divine word, the Qur’an. It is an artistic expression for the love of wisdom. The immediate impressions that capture the receiver—with the eyes, mind, heart, and soul—inside of them are, no doubt, a moment of infinity. That moment of receiving is not just related to the artistic labor. In itself, it is a product of the experience itself: the primal experience of dealing with the divine word and reaching beyond it. Arabic calligraphy is an artistic medium with which the Muslim artist was equally vanished and overwhelmed, exterminated and flooded, fashioned and ended in dealing with the scripture. (Ebeed, 2005)

Ibn Muqla actually developed the handwriting to its current form, distinguishing it from other handwritings. It was named Naskh (meaning “copy”) because writers used it in the copying of the Qur’an, the Hadith, and other books. It was also used in writing on metal, wood, marble, and plaster.

Naskh script is considered as an element of decoration and gained much attention in Iraq in the Abbasid era. It was used in the writing of the Qur’an in the Islamic middle ages and it replaced the Kufi script for copying the Qur’an and decorating the walls of the mosques. Both Naskh and Thuluth became the most prevalent scripts. Naskh can be differentiated from Thuluth by the small size of its letters. The size and sequence mean the writer can use the pen more swiftly than when writing the Thuluth, but still retain harmony and beauty.(Ebeed, 2005)

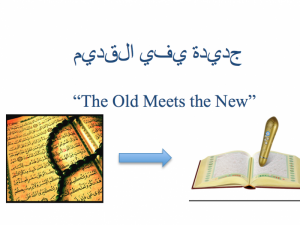

Multilingual Digital Koran:

Haji Arafat Shaikh, a Mumbai entrepreneur, has introduced a multi-lingual digital version of the Holy Koran for the benefit of Muslims in multiple countries. The device operates by simply placing the pen on the Koran and it will automatically start reading it in the desired language. The reader was designed to be user friendly, which allows the device to be operated by a wide variety of ages. The languages offered include Hindi, Urdu, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali, Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, French, Chinese and Pashto.

Considering that the Arabic language is very challenging to learn, this is a huge step towards attracting Muslims in larger countries like France and China. This device targets those individuals who do not understand how to read the Holy Quran in Arabic language. Interest in Islam is rising among Hong Kong’s Chinese population, with more joining courses about the religion. There has been a steady number of converts, and there are currently more than 300,000 Muslims living in Honk Kong. In France, Islam is the second-most widely practiced religion in France behind Roman Catholicism by number of worshippers, with an estimated total of 5 to 10 percent of the national population.

So what effects will the multilingual digital Koran have on the growth of Islam? Assuming specialized training will be available, the reader will be the root cause for mass growth of the Islamic faith in both the west and the east. For example, children living in China whose parents practice Islam will not have to learn how to read and write Arabic, but they will be able to read the Koran in Chinese via the pen and reader. Because of this, these children will comprehend the context at a quicker pace, and become more proficient with the Islamic faith at an earlier age. Because the reader also offers the Koran in French, this same scenario could occur in European countries as well. There is no question that Islam is the fastest growing religion in the world, and devices like the multilingual digital reader will help increase the growth in emerging countries throughout the world.

References:

Belt, D. (2002). The World of Islam. National Geographic, 201(1), 76.

http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=5&sid=c4112829-6254-47f6-b5c4-2a17d5791266%40sessionmgr4&hid=124&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwJnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#db=aph&AN=5700395

Ebeed, A. (2005, February 27). The Naskh Script: The Servant of the Qur’an. Retrieved from http://www.onislam.net/english/reading-islam/research-studies/art-a-architecture/441737.html

Ebeed, A. (2005, February 27). Arabic Calligraphy: The Essential Islamic Art. Retrieved from http://www.onislam.net/english/shariah/contemporary-issues/human-conditions-and-social-context/413234.html

Chemnad, K. (2006). The origin of arabic calligraphy. Retrieved from http://www.worldofcalligraphy.com/article1.html