SPOILER WARNING

As with every entry on this blog, this SLIME analysis is going to be delving into core parts of the setting, characters, and overall narrative of this game. As a result, this analysis (and any others subsequent) will spoil major plot points for any who have not yet played this game. If you’re approaching this analysis from scholarly curiosity but have not experienced the game yourself, please do so before continuing. If you intend to use this game as a learning experience and literary connection, please read on.

As with every entry on this blog, this SLIME analysis is going to be delving into core parts of the setting, characters, and overall narrative of this game. As a result, this analysis (and any others subsequent) will spoil major plot points for any who have not yet played this game. If you’re approaching this analysis from scholarly curiosity but have not experienced the game yourself, please do so before continuing. If you intend to use this game as a learning experience and literary connection, please read on.

CONTENT WARNING

Planescape: Torment has been rated T for Teen by the Entertainment Software Rating Board for Animated Blood, Animated Violence, and Suggestive Themes. This game is not appropriate for all audiences and all age groups. If you intend to use this game as an example, learning tool, or literary connection, please ensure that your students or audience are at a developmentally-appropriate maturity for this content.

Planescape: Torment has been rated T for Teen by the Entertainment Software Rating Board for Animated Blood, Animated Violence, and Suggestive Themes. This game is not appropriate for all audiences and all age groups. If you intend to use this game as an example, learning tool, or literary connection, please ensure that your students or audience are at a developmentally-appropriate maturity for this content.

PLANESCAPE: TORMENT

Planescape: Torment is what could be considered—in gaming circles—a cult classic. Much in the way that films can lack broad popularity but be deeply loved by a dedicated few, Planescape: Torment is a game that did not enjoy financial success but rather critical success.

In genre terms, Planescape: Torment is treated as a Role-Playing Game (RPG). To the outsider, this name might seem redundant; all video games require you to take on the role of a character. In this case, however, the etymology of this genre derives from pen-and-paper tabletop role-playing games in the style of Dungeons & Dragons. Players take on a given persona and play it out in a fictional setting, with all of the conversations, choices, and combat that might entail. Indeed, the first part of the title—Planescape—is itself a fictional setting for Dungeons & Dragons wherein role-players can create characters and embark on adventures.

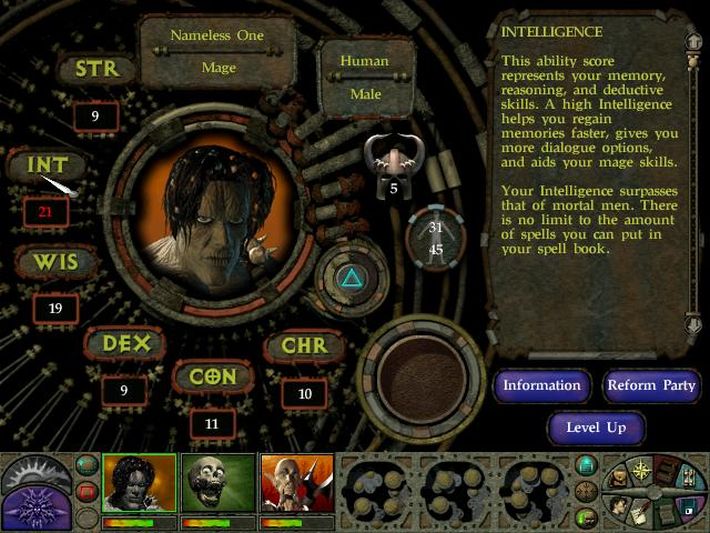

In terms of actual play, Planescape: Torment is not a high-speed action game. The underlying mechanics hearken back to the tabletop games from which it inherits. Success or failure on a test of strength or intelligence is resolved via an invisible dice roll, and even though—to the player—battles against enemies seem to take place in real-time, beneath the surface the characters are taking turns attacking and defending much as one would in a real session of Dungeons & Dragons. Much as one would play Dungeons & Dragons with a group of friends, cooperating to embark on an adventure, players in Planescape: Torment are accompanied by a group of other characters—with their own personalities, motivations, and histories, no less—who face challenges alongside the player (or even present new ones!).

Rather uniquely among sword-and-sorcery fantasy games—and even Dungeons & Dragons-style games in particular—players in Planescape: Torment are not best served by bulking their character into a mighty warrior, arming them with enormous weapons and charging into combat at every opportunity. Planescape: Torment is very heavy on conversation; veteran players will tell you to develop your skills in lore and conversation and intelligence instead of the skills that let you win fights. Some of the game’s core themes speak to notions of memory and immortality, so whether you can recall a fact or solve a problem is much more useful than being able to win a fight. Often the most expedient, beneficial, and personally gratifying way to solve a crisis in Planescape: Torment is to talk it out.

A game so steeped in strange lore and extensive, complex conversations is rich in philosophical and literary significance and a natural starting point for those wanting to explore the validity of video games as an art form. With that in mind, let’s delve into the SLIME:

SETTING

Planescape: Torment’s primary setting is a city called Sigil. Even for those deeply inculcated in fantasy lore, Sigil is a bizarre, alien place. It stands at the convergence of all the planes of reality (alternate dimensions, more or less—this is part of why the setting is called Planescape). Sigil is known in the Planescape world as “The City of Doors.” Since it essentially sits between all of the different realities, it has become a place to enter and exit different planes of reality—whether intentionally or unintentionally! Despite the name, the nature of the portals that will take you to different worlds is far stranger than that of a simple “door.” Most anything can serve as a portal to another world if you know how to unlock it, and many travelers have fallen into or out of different realities by stumbling upon portals by accident. Indeed, many of the characters that the player meets in Sigil are foreign to it—for example, the brash, stereotypical adventuring warrior who thinks that Sigil is just another scary place to explore, or the terrified woman trying to find her way back to her home after landing in Sigil by accident.

LITERARY BRIDGE

Literature is full of unwitting doors to fantastical places, so despite how utterly alien it is, Sigil’s nature as a place of doorways may be familiar to some. Consider, for example, Lewis Carroll’s myriad portals in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Indeed, the sequel is entitled Through the Looking-Glass, a direct reference to the very mundane object that turns out to be a portal to another world. Later works—typically children’s literature—would use this device; recall also the titular tollbooth in Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth or the titular wardrobe in C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Behold the bizarre complexion of the Alley of Dangerous Angles.

Beyond being a conduit to all sorts of strange worlds, Sigil itself is on its own terms deeply bizarre. Given that it is by its nature a melting pot of all sorts of fantasy creatures—demons, talking skulls, living machines—the culture and sociology that Sigil breeds is exceedingly strange. Not only are the inhabitants alien, so too is the city itself, as it is just as alive as anyone else. Streets seem to rearrange themselves, and one section that the player must pass through (called the “Alley of Lingering Sighs”) is capable of speaking to the player by scraping wood and stone together in a mimicry of speech. In fact, the Alley beseeches the player for help: it must “divide” (i.e. give birth) and needs the player to remove meddlesome repair workers before it can proceed! In this way, Planescape: Torment allows even a problem such as clearing a road to pass through it to be solved via conversation.

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

Many fantasy works desire to describe fantastical, wondrous, and sometimes terrifying places; making the place itself “alive” is an easy method of doing so. The most immediate and familiar point of comparison is J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series; the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is by turns haunted by ghosts and filled with living architecture and statues.

LEAD

Unlike a typical game of Dungeons & Dragons, players do not begin by creating a character from scratch. The lead character of Planescape: Torment is The Nameless One, a character that—unbeknownst to the player and, until late in the game, himself—has a long history and has already left an indelible mark on the Planescape world. True enough that once the player is able to take control of him that his future actions are in the player’s hands, but both he and the player must take care to unravel his prior history; The Nameless One might have forgotten his past, but others he has met before have not.

Behold The Nameless One. Not a looker, this guy.

When the game first begins, The Nameless One awakens on a slab in a crematorium. He is, in fact, recently dead with no memory of his past or even his name (thus the game’s internal name for him). Death doesn’t seem to have been an impediment, as he climbs down off the slab, alive and well, to find out what has happened to him. His first source of information is Morte, a floating, talking, sarcastic skull who will accompany The Nameless One throughout the rest of the game. In a rather unexpected (and somewhat macabre) twist, Morte discovers that The Nameless One has written a note to himself—in his own flesh with a knife, no less. All at once, and from the beginning of the game, the core traits and motivations for The Nameless One are set: he cannot die and does not remember anything.

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

Amnesia is a fairly common fictional device, but not actually very prevalent in major literature. More commonly, it’s seen in television and film. One very familiar intersection in both literature and in film is Robert Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity (to say nothing of its sequels and their adaptations). Jason Bourne’s remarkable (though ill-understood) abilities echo The Nameless One’s own (similarly ill-understood) powers, and both of them are driven by a need to piece together their past.

The Nameless One’s immortality is not completely absolute; if his body is burned away or if he is destroyed by a creature of unfathomable power (for example, The Lady of Pain, the silent and enigmatic overseer of Sigil), he will be dead for good. In all other circumstances, however—whether stabbed by knives, smacked with maces, or zapped by magical spells—he will wake up a few hours after his death, achy but alive. This has fascinating gameplay implications. Not only is the price of failure lessened (why not try a crazy plan that might kill you if killing you is meaningless?), but death itself becomes a solution to problems. Perhaps there’s no good way to sneak into somewhere you’re not supposed to go, but who’s going to presume you’ll wake up again behind enemy lines if you’re smuggled in as a corpse?

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

Immortality doesn’t make a terribly frequent appearance in literature, the aforementioned J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series aside (consider the notion of Horcruxes and how they allow Voldemort to rise from the dead even though his body is killed). It is, however, a frequently-invoked concept in mythology. Common vampire myths hold that—much like The Nameless One—there are very specific actions that must be taken to truly kill a vampire for good. Consider also the nature of the hydra in Greek mythology. Much as The Nameless One can ironically benefit from a killing blow, so too can the hydra: if one head is chopped off, two will grow in its place. Bad for its intended slayer, but good for the hydra!

INFLUENCE

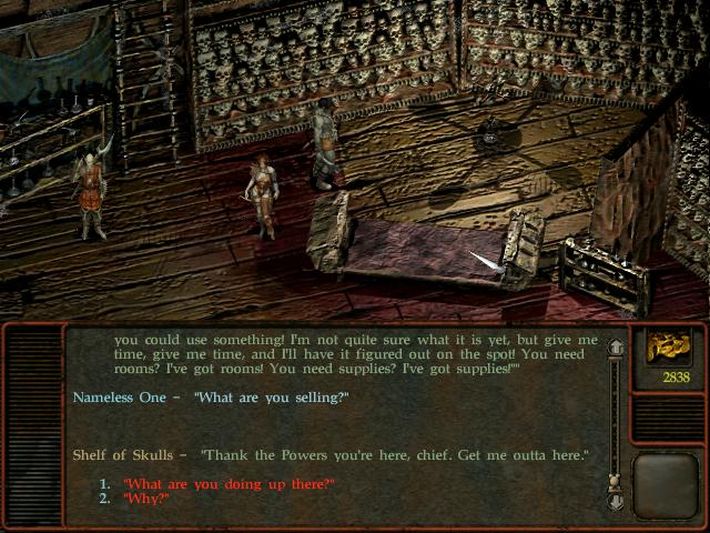

As with any game, the player is not a passive observer. Not all games, however, go to the depth of influence and agency that Planescape: Torment does. In the first place, being a conversationally-focused game means that your primary interactions are with people, not with faceless monsters or traps. As a result, merely talking to people means that you can convince, intimidate, coerce, deceive, or exhort them in order to meet your ends. You could charge headlong into the Warrens of Thought, laying waste to every Cranium Rat you encounter—and why not? Cranium Rats are filthy, hive-minded spell-casting rats! Then again, they’re mind readers… you could always try talking (or rather, thinking) to them. Behave antagonistically and get captured, and you’ll have to fight your way out of a dangerous dungeon. Behave congenially and talk it out, however, and your life becomes much easier.

More neighborly to talk Lothar the Master of Bones into giving you your talking skull back than to club him in the head.

Interaction also extends to your companions in your adventuring party. Your party can easily turn into a rather eclectic group; you can recruit Morte the snarky talking skull, Dak’kon the monastic warrior-mage, Annah the half-demon cutpurse, Fall-From-Grace the benevolent succubus, Ignus the pyromaniac wizard, Nordom the living machine, and Vhailor the merciless haunted suit of armor. All have unique motivation and histories, and some of those histories overlap with The Nameless One’s. For example, Morte accompanies The Nameless One to atone for getting him killed earlier, and Dak’kon is essentially bound to The Nameless One in servitude from a previous incarnation. The ways in which you interact with your companions can alter their behavior, sometimes in dramatic fashion; mishandling your interactions with Vhailor will result in him trying to kill you!

Many games allow you to influence events by slaying foes, persuading characters in conversation, or by choosing sides in politics or war. Planescape: Torment, however, is unique in how the setting allows for additional means of influence. In the Planescape world, reality can be altered by thought. In one early interaction, a character named Mourns-for-trees is (fittingly) despairing that his trees are dying. The best means to help him is through exerting sheer belief (and inspiring your companions to do the same) that the trees can thrive. In more dramatic fashion, you can also believe other people into or out of existence. The Nameless One has no name, and if you use a pseudonym (specifically, “Adahn”) too frequently, a man will appear from nothing with that name. Even more dramatically, the final foe of the game can be defeated by the belief that he doesn’t exist. With enough belief, it suddenly becomes true.

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

A natural connection to the notion of belief shaping reality is the nature of fairies in J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. Disbelief in fairies can kill them, and belief can bring them back to life. Many of the cosmological underpinnings of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series also operate on this notion, especially where the gods are concerned: their actual legitimate powers wax and wane depending on the faith of their supplicants. The titular antagonist of Stephen King’s It has a habit of taking the form of creatures from folklore, and sufficient belief in that folklore allows its enemies to fight back in the same fashion they would for the creature invoked (e.g. silver bullets for a werewolf, etc.). Power of belief, naturally, plays a frequently literal role in many religious texts, but this may not be an easy literary connection to explore.

MISSION

As previously mentioned, one of The Nameless One’s core motivators is the endeavor to piece together his own memories of his history. The nature of this amnesia, its place as a motivator, and its literary connections have been previously examined. Perhaps more interesting (and certainly more emotionally compelling) is what drives The Nameless One once his memories start to return to him. As you progress, you discover a multitude of disconcerting repercussions of his immortality. Once a mystery, his ability to return from death is revealed to be self-inflicted. Purportedly, whoever The Nameless One was in life was so unforgivably cruel and malevolent that he would be guaranteed damnation in the afterlife. In truth, The Nameless One himself sought (and achieved) immortality in order to garner sufficient time to atone for his sins and prevent his own damnation. Unfortunately, this immortality brings him no closer to absolution; not only does death affect his memory, but his resurrection—long unbeknownst to him—requires the sudden death of another. While the short-term mission of The Nameless One is self-understanding and a reassembly of his memories, his long-term mission (predating even the game itself!) is atonement. In the end, his immortality poses an impediment to this atonement: at long last, his only solution is to cast off his immortality, die, and pay for the sins he committed (and the incidental sins from his resurrections causing others to die) in the hellish Lower Planes.

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

The Nameless One’s myriad motivations are all thoroughly represented in literature, whether in the initial commitment of an unforgivable crime (consider Ender Wiggin’s genocide—and need to atone!—in Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, Voldemort’s unspeakable reputation in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, Napoleon the pig becoming worse than his oppressors in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, literally anything Joffrey Baratheon does in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire novels, etc.) or immortality carrying such a heavy cost that it ends up deepening sins (consider Voldemort—again—as well as Herbert West’s willingness to kill for his experiments in H. P. Lovecraft’s Reanimator).

ENEMY

Befitting a fantasy role-playing game, the foes one encounters in Planescape: Torment—conversation-heavy though it is—range from the mundane to the monstrous. Depending on how belligerent you choose to be, you can do battle with common street thugs, shambling zombies, grotesque demons, zealous cultists, and ghastly spectres. If you’re unfamiliar, rest assured that this is all rather par-for-the-course for a fantasy setting, especially in video games. More compelling is the game’s main antagonist.

As previously mentioned, The Nameless One inflicted immortality on himself in the hopes of atoning for past sins, but the player eventually discovers that the only means of ensuring his immortality is to violently remove his mortality from his body (a feat performed by Ravel Puzzlewell, a powerful witch who also appears in an antagonistic role in the course of the game). This mortality—once removed—did not disappear. Instead, it became a living being unto itself. This being (which the game calls The Transcendent One), in its own fear of death, constantly undermines the efforts of The Nameless One to reassemble his memories. Remembering enough of his past could allow The Nameless One to seek out and destroy The Transcendent One to undo his own immortality, and so The Transcendent One kills friends, acquaintances, and even The Nameless One himself (thereby invoking amnesia) to ensure that he has no way to reassemble his memories.

Confronted by the ghosts of the people who have died due to The Nameless One’s resurrections. In truth, The Transcendent One has sent them to murder him into amnesia again.

Keeping in the spirit of Planescape: Torment, there are multiple ways to contend with The Transcendent One that don’t involve fighting. As previously mentioned, you can use the power of belief to undo his existence (and therefore, unfortunately, your own). More interestingly, you can also use logic and compulsion to drive him to merge his body back into The Nameless One’s, thereby undoing his mortality and allowing him to die and serve his penance in the afterlife.

LITERARY BRIDGE

LITERARY BRIDGE

The nature of The Transcendent One is unique enough that literary parallels can be hard to draw. It may instead be easier to draw parallels to underlying questions or character actions. For example, the decision whether to suffer through hell or simply cease to exist is one contended with by the fallen angels in John Milton’s Paradise Lost, and the use of talk to defuse a threat is a common archetype (as one example among many, consider Bilbo’s coercion of Smaug in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit in order to keep from being devoured).

CONCLUSION

A proper in-depth analysis of Planescape: Torment would require more space than I have here and more heads than just my own. It is a lengthy, lore-rich game whose best qualities are brought to the surface by conversation, not violence. There are many, many more significant themes to unearth and discuss, and I hope you will take the opportunity to play the game yourself and see what speaks to you.