Written by: Elizabeth Bocksenbaum | Spring 2023

ISEP Exchange at the University of Malta

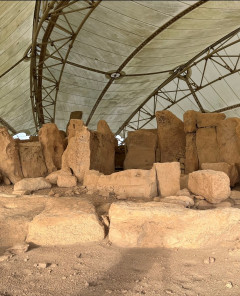

When coming to Malta, I expected to appreciate the history and practice the principles I learned as an anthropology major. I knew the Island had been described as a living museum and had worked to preserve many incredible archaeological sites and historical buildings. Little did I know how my courses at the University of Malta would connect me directly to the people and narratives that heavily developed the ways in which archeology is performed globally. I also wasn’t anticipating the closeness I would have to see the historical sites and artifacts that made this Island so important in history.

Within my first week of classes, I discovered that each of my archeology professors were active participants in the ongoing digs and archaeological research throughout Malta. Not only do some of the professors actively work on the Maltese sites, but they encourage current students from the university to work on digs with them to gain field experience. Other professors produce main academic journals and excerpts that update the research of the Maltese archeological sites. Because of this close connection to the archeological sites and research on the Island, many professors will even incorporate Maltese archeological history into lectures as a main point of reference. For every archeological concept given in a history lecture, a reference to Malta is used to further explain and provide context to a specific practice.

Not only was I amazed by the direct connection to the archeological sites and research in Malta, but how fully immersive my experience was in understanding the practice and art of archaeology. Throughout my weekly lectures, I go from understanding the development of archeology, seeing how research translates into our understanding of ancient civilizations, learning how to draw and scale pottery and artifacts, to physically conserving and strengthening historical books and documents in the National Library in Valletta.

For my archaeology theory course, I learn about the foundations of archaeology and how it has developed into the ever-changing process it is today. I then take these ideas to my Ancient Civilizations of the Mediterranean course and my Ancient Israel course and attempt to understand the records and information found on groups of ancient peoples. Later in the week, I take a course on how to draw different artifacts with tools and record them into a digital archeology database. I then take all this information into my conservation placement where I work with the National Library in Valletta and help conservators conserve historical documents and books. Once my classes are done for the day, I then get to explore the different museums and historical sites on the Island and see how the content of my lectures manifests into the physical displays of archaeology. By the end of the week, I not only learn about the history of archeology and Mediterranean discoveries, but the ethnocentric perspective of how an archeologist theorizes, performs, and perceives. Ultimately gathering an anthropological insight into a very anthropological field.

In my experience, the most beautiful part about the archaeology in Malta is that it is far from being done. When Maltese archeological sites were first excavated in the mid-1800s, most of the remains found were simply thought to be just Phoenician. The idea was that remains found in the west were believed to always be newer and remains found in the east would always date older. When the use of Carbon dating was developed after World War II, the entire dating system used to identify archeological remains and sites was completely demolished and renewed. When carbon dating was applied to the remains found in these Maltese sites, it revealed the sites to date back to 3600 BCE, older than the great Pyramids of Giza in Egypt. This discovery not only changed Maltese practices of archaeological dating, but the principles used to develop archaeology as a whole.

This discovery still influences the ways in which archaeology is practiced in Malta through the displays presented next to archaeological remains in museums. When walking through the National Museum of Archeology in Valletta, you can see a diverse set of artifacts and pieces of architecture on display along with signs that admit the lack of information on particular pieces. The beauty in this is the acceptance of a need for further research rather than blindly guiding guests into believing we have discovered everything there is to know about the archeological sites and artifacts. Not only is this practice displayed in the museums, but is heavily reflected in the lectures I take at the University of Malta. While there had been many discoveries in the archaeological community in Malta, there will always be more perceptions, practices, and principles to discover and consider.

The entire experience moves full circle and brings me back to the initial excitement of coming to this Island. From the personal relations with the professors and conservationists, the physical practices of conservation and archeological illustration, to the exposure of historical sites and museums, my time in Malta has provided an immersive archeological experience that has developed the ways in which I appreciate the practice of anthropology and archeology. While the art of archaeology may begin with the physical remains and structures of the past, it continues to be fueled by the ever-changing perspectives and practices of people.