References for this site are listed below:

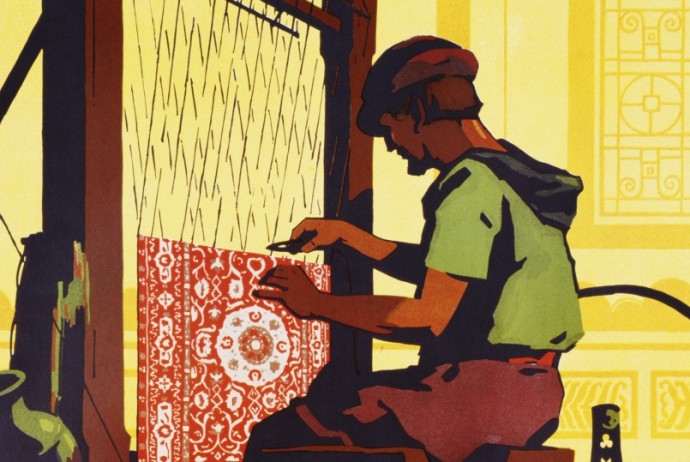

Textiles:

Audrius Meskaukas. (n.d.). [Photograph of The Flying Shuttle].Retrieved from http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/009.html under Public Domain License.

Black Stripe. (August 2007). [Photograph of A working Mule spinning machine at Quarry Bank Mill].Retrieved from http://history.parkfieldict.co.uk/victorians/victorian-cotton-mills under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Unknown Photogrpaher. (n.d.). [Photograph of The Spinning Jenny].Retrieved from http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/010.htmll under Public Domain License.

Unknown Photographer. (n.d.). [Photograph of Textile Mill].Retrieved from http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/014.html under Public Domain License.

Unknown Photogrpaher. (n.d.). [Photograph of The Water Frame].Retrieved from http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/011.htmlunder Public Domain License.

USDA photogrpaher. (n.d.). [Photograph of Cotton Plant].Retrieved from http://history.parkfieldict.co.uk/victorians/victorian-cotton-mills under Public Domain License.

Martin, D. (1983, April). The Industrial Revolution: Toil & Technology in Britain & America. History Today, p. 24.

O’Brien, P. (1991, August). Political components of the industrial revolution: Parliametn and the English cotton textile industry, 1660-1774. Economic History Review, pp. 395-423.

Burchill, S. (2013). Brief History of the Cotton Industry. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from The Open Door Web Site: http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/014.html

Burchill, S. (2013). The Flying Shuttle. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from The Open Door Web Site: http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/009.html

Burchill, S. (2013). The Spinning Jenny. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from The Open Door Web Site: http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/010.html

Burchill, S. (2013). The Water Frame. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from The Open Door Web Site: http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/011.html

Iron:

Burchill, S. (2013). Iron and Steel Manufacture. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from The Open Door Web Site: http://www.saburchill.com/history/chapters/IR/037f.html

English Online. (n.d.). Industrial Revolution. Retrieved April 12, 2014, from English Online: http://www.english-online.at/history/industrial-revolution/industrial-revolution-manufacturing.htm

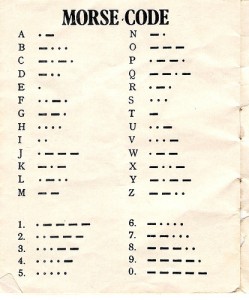

Telegraph:

Morse Code and the Telegraph. (n.d.). Retrieved April 8, 2014, from History: http://www.history.com/topics/inventions/telegraph

Telegraph and Telephone. (n.d.). Retrieved April 16, 2014, from Know It All: http://www.knowitall.org/kidswork/etv/history/telegraph/

Morse Code [image]. (n.d.). Retrieved April 16, 2014, from Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/coxar/310256170/in/photolist-tq9mj-7G94qm-aQ9H5-6p5FYG-8xMcDf-FEzZ1-2rA36-5jQxdQ-4oDRaV-4ctVpa-6u1uVu-3f4R3X-vLQdu-5jgwr-d3HCsw-bAoAAd-ccwA7s-4DNsH9-7zeveS-guF4hi-5d9MuV-5WHKgk-6jchje-5dbzDR-5z2KXV-5dfUvC-5dfUyW-doxY9t-5E1tdC-8NKYyr-8NKZcR-57pcKr-5rwDWF-5EkJ3s-e7LeVz-kU9Dbt-3hH2TL-4JRzgb-eUiF4p-4RD6CE-2btBF1-8NFM14-e7S77b-4JRzkJ-dbPXiX-P5BNh-5EkJ3q-5uye5m-4NZTmG-duu7AyURL

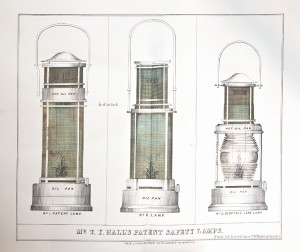

Mining:

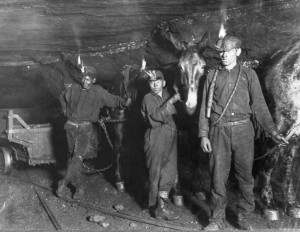

Coulson, M. (n.d.) The History of Mining: The Events, Technology and People Involved. Retrieved April 8, 2014

Steel:

Unknown Photographer. (July 1920). Barrow Haematite Iron and Steel Works, Barrow-in-Furness, from the West, 1920.[Photograph]. Retrieved from http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/image/epw004059 under Public Domain License.

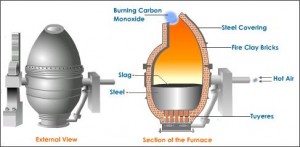

Raju. (24 November 2010). The Bessemer Converter Bessemer Process. [Illustration]. Retrieved from http://belajar-engineering.blogspot.com/2010/11/bessemer-process-bessemer-converter.html under Public Domain License.

Paul, A. (15 July 2005). Rail Made by Barrow Steel in 1896. [Photograph]. Retrieved from http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/87/Rail_Barrow_Steel_1896.jpg under Public Domain License.

Adams, M. (27 September 2012). The Industrial Revolution in Germany. Retrieved April 12, 2014 from http://www.humanities360.com/index.php/the-industrial-revolution-in-germany-2-5777/#sourcesAndCitations

Dahlen, M. (Fall 2010). The British Industrial Revolution: A Tribute to Freedom and Human Potential. The Objective Standard Fall 2010: 47+. Student Resources in Context. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

Henderson, J. (10 April 2014) The Industrial Revolution. Retrieved from http://www.historyhaven.com/APWH/unit%204/THE%20INDUSTRIAL%20REVOLUTION.htm

Mokyr, J. (August 1998). The Second Industrial Revolution, 1870-1914. 10. Retrieved April 10, 2014 from http://faculty.wcas.northwestern.edu/~jmokyr/castronovo.pdf

Open-Hearth Process. (2014). In Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved fromhttp://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/429666/open-hearth-process

Quitney, J. (2014, January 29). How Steel Is Made circa 1943 Bethlehem Steel. Retrieved April 13, 2014 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKBMRL2Pnf8

Other:

A&E Television Networks, LLC. (2014). Industrial Revolution. Retrieved March 28, 2014, from History: http://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution

Unknown Photogrpaher. (n.d.). [Photograph of Books].Retrieved from http://thinkteachinspire.com/2013/01/02/putting-exceptional-back-in-america-its-what-great-schools-do/under Public Domain License.