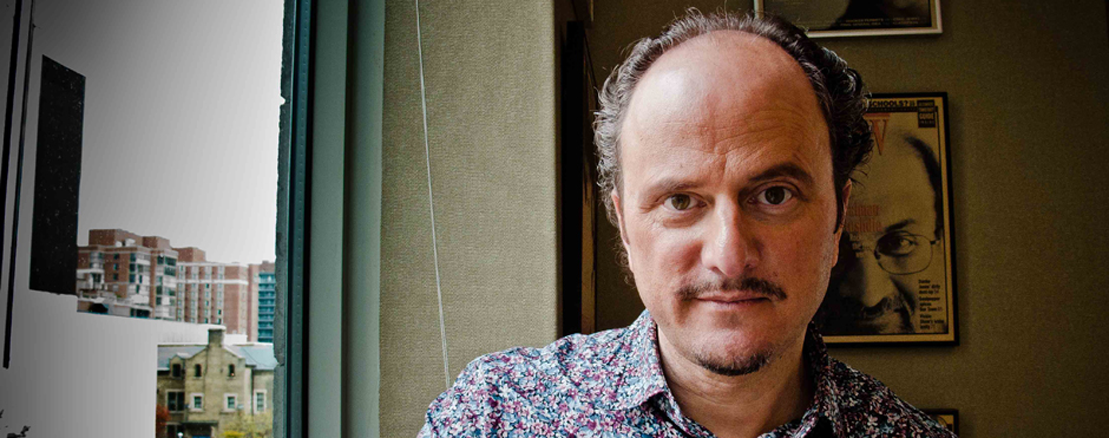

Less than a week removed from D.A. Powell’s VWS season opener, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jeffrey Eugenides will be joining us Monday, September 16 at 7:30 in Atherton’s Reilly Room. Author of novels The Virgin Suicides, Middlesex, and most recently The Marriage Plot, Eugenides publishes essays and short fiction as well, and has an untitled short story collection forthcoming. (If aspiring writers wish to know how many novels you must publish before you can sell a short story collection, the answer is three, provided one is filmed, and two win outlandishly prestigious awards. Godspeed.)

However, with a Pulitzer under his belt, a Guggenheim Fellowship and a National Book Critics Circle Award, I’d wager Eugenides considers his most important achievement the selection of his sophomore novel Middlesex to Oprah’s Book Club.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Eugenides cites his influences as modernists Joyce, Proust and Faulkner, as well as Woolf, Musil, and Pynchon. He explains, “My generation grew up backward. We were weaned on experimental writing before ever reading much of the nineteenth-century literature the modernists and postmodernists were reacting against.” This literary pedigree may just help explain how and why he, as an unproven young author, penned his debut novel in first-person plural.

Eugenides’ follow-up Middlesex is an entirely different beast. It is the story of the Greek-American experience, but also the intersex experience. While Eugenides trades in the daring POV of his debut for more ‘traditional’ third-person narration, that narration jumps in and out of heads as necessary. That narration is omniscient unless the story demands it be limited. That third-person is unbounded by the confines of gender: Callie fluidly transitions into Cal. Put plainly, I lied when I wrote the word traditional.

In Middlesex, Eugenides’ prose is somehow lush and utilitarian, somehow indulgent and exacting. The book feels as though it could be much shorter, but the reader feels that any the loss of any insight or peculiar detail, any knee bump, tummy slap or long parenthetical, would be a small tragedy in itself.

His control of structure is to be admired as well. The titular chapter has this consummate sense of balance. It opens with Callie tracking her own growth via her father’s yearly car trade-ins, counting up from ’67 to ’74, but it closes with Callie tracking her grandfather’s mental decline, first subtracting single years, then entire decades. It opens with the family coming into money and buying a suburban home, but it closes with Callie’s grandmother turning the guest house into a tomb.

And at the center of all of this, a precipice: olive-skinned, seven year-old Callie “practice kissing” with fair-skinned, “worldly,” eight year-old Clementine. It is innocent, but it is a loss of innocence, a lifted veil, a singular moment that combines the Greek-American narrative, the intersex narrative, and a point of no return both in micro- and macrocosm. An excerpt from the scene follows:

She hoots like a monkey and pulls me back onto a shelf in the tub. I fall between her legs, I fall on top of her, we sink… and then we’re twirling, spinning in the water, me on top, then her, then me, and giggling, and making bird cries. Steam envelops us, cloaks us; light sparkles on the agitated water; and we keep spinning, so that at some point I’m not sure which hands are mine, which legs. We aren’t kissing. This game is far less serious, more playful, free-style, but we’re gripping each other, trying not to let the other’s slippery body go, and our knees bump, our tummies slap, our hips slide back and forth. Various submerged softnesses on Clementine’s body are delivering crucial information to mine, information I store away but won’t understand until years later. How long do we spin? I have no idea. But at some point we get tired. Clementine beaches on the shelf, with me on top. I rise on my knees to get my bearings—and then freeze, hot water or not. For right there, sitting in the corner of the room—is my grandfather! I see him for a second, leaning over sideways—is he laughing? angry?—and then the steam rises again and blots him out.

I am too stunned to move or speak. How long has he been there? What did he see? “We were just doing water ballet,” Clementine says lamely. The steam parts again. Lefty hasn’t moved. He’s sitting exactly as before, head tilted to one side. He looks as pale as Clementine. For one crazy second I think he’s playing our driving game, pretending to sleep, but then I understand that he will never play anything ever again…

And next all the intercoms in the house are wailing.

Before I leave you, allow me to just dig out the line: “Various submerged softnesses on Clementine’s body are delivering crucial information to mine, information I store away but won’t understand until years later.” Part of what we as readers seek in literature is new experiences that are outside ourselves (and the affirmation of ones that do exist inside). Middlesex, and really, much of Eugenides’ corpus, blends rich, lyrical prose with such perfect little idiosyncrasies like the line above. Beyond appreciating his words, there’s discovery in his work, playfulness.

And you have the chance to not only be in the same room as him, but hear him read, plumb his brain with a question or two. On Monday. 7:30. Reilly Room. Be there, or be prodded in your submerged softnesses.